Three weeks in Beijing have passed quickly and tomorrow I leave for Shanghai and the whole Expo experience. As always, being in China has taught me a lot about myself, my habits and preconceptions, nowhere more so than in relation to traffic and travel.

I spent the first week waiting for Platform China whose studio that I’m staying to provide the promised bicycle and in the meantime took a lot of buses in and out of town. I hated having to wait, being constrained by an unfathomable timetable and being jostled and squashed. When Platform China couldn’t provide a tall enough bicycle, I rented one myself (of course now I am wiser thanks to everyone’s post factum counsel that it would have been cheaper to buy a bike than rent one). Having a bike restored my much valued independence. It’s clear to me that I am willing to expend a considerable amount of physical energy to secure that independence as I have cycled hour long trips across the city rather than subject myself to buses or even the uncertainty that a taxi might be taking you for a ride. So that’s one lesson about independence.

The other thing I learned cycling in Beijing is about improvisation. The rules of the road are baffling to me – more baffling than the language. People cycle the wrong way, pedestrians walk in the middle of the road and with passive aggression ignore the constant hooting of cars and bikes. Buses pull in in front of you, pinning you to the kerb and then stop but pull out again when you try to overtake them. Since the choreography isn’t clear to me, I have to improvise, alongside everyone else who seems to be improvising. I imagined that this improvisation had a structure, a set of shared rules which I might not know but I assumed everyone else did. However, when I see the accidents, the battered cars and the injured cyclists, I do wonder if that’s the case. More than anything I am ground down by what appears to me to be the discourtesy of such lawlessness. Whether or not I am completely misreading the situation, it is the fact of this care for courtesy that I notice in myself. Courtesy of course doesn’t leave much room for surprises.

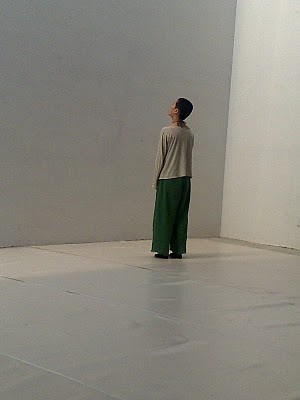

I think about improvisation because working with Xiao Ke on Dialogue for the past two years has been the most sustained engagement with improvisation that I have undertaken. I have grown more comfortable with the process but only after we’ve established clear parameters for the improvisation. This version of Dialogue which we will perform in Shanghai has two new artists involved: Feng Hao, an experimental musician who is making a name for himself on the improvised music scene in Beijing and He Long, a video artist who does a lot of live visuals for music events. Both have brought a youthful energy to the piece. Meanwhile Xiao Ke and I have refined the structure of the piece, simplifying the line and relaxing in to our growing familiarity with each other.

My tai chi and qi gong practice have given me access to a different movement style that I’ve used a lot in Dialogue. In previous versions I was anxious about representing the kind of muscular physicality that I had considered a hallmark of my work. Now I don’t feel the need so much to that. Maybe I’m older. Maybe I’m tired. Maybe it just isn’t necessary.

With Match and Niche to perform after Dialogue, however, I’m curious to see whether I can still tap in to that muscular engagement upon which Match in particular was constructed.