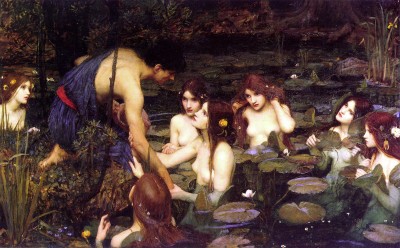

Coming back to our Moving Layers R&D, I felt some pressure to round it up, to turn it into an outcome, despite realising that two weeks of a very new kind of R&D was very preliminary. Often when we do R&D for a performance, the research is towards a relatively defined destination with relatively familiar tools and resources: the trajectory of the research is linear. In this case, however, the research and the consequent learning was multi-dimensional: we aimed towards some kind of scratch performance outcome, but that was to give ourselves forward momentum rather than a destination. We didn’t know what the performance outcome/event/experience would be. Our previous sharing suggested that the value of dancing remained at the heart of the work but what else could it be? We didn’t know what form it might take, nor what its content/subject might be. Through Hylas and the Nymphs we gave ourselves a focus (seduction, immersion, desire, fluidity, transformation) that also reflected on the process we were involved in, allowing us to see ourselves considering the interface between the live and the augmented and to see bodies being transformed by the interaction with the technology.

Alongside that evolution of process and content, we also continued to get to know each other. With a new duo of dancers – Theo Clinkard and Folu Odimayo – there were conversations to repeat and in the process deepen as we introduced the process to new people and opened to their perspectives. We continued to work out the rhythms of a rehearsal process with dancers and, in this week, a composer (Tic Ashfield) and a developer (Roderick (Rob) Morgan) in the room.

While much composition and coding could happen before or elsewhere, I know from working with Tic (and with Alma Kelliher) the benefit of having the composer in the room, soaking up information that might not be articulated otherwise, sharing physical and affective space. I think the same is true of having a developer in the rehearsal room. Even though Rob Morgan was busy with the coding, often focused on the laptop rather than the moving bodies, having him with us, sensing the energy in the room, created human links that fed the work. It’s the preciousness of affective, kinaesthetic, embodied connections that we took care to maintain in our R&D, despite the seductions of the augmenting technology. We wanted to use the technology to help an audience to step from viewing to dancing, to use the distraction of augmentation to give people three-dimensional scripts and visual rhythm to prompt their movement.

We also discovered that for an audience, the technology – in particular the Hololens headset – can stimulate the viewers’ imaginations even if they’re not wearing it. They imagine what the Hololens wearer is seeing, maybe desire to see, and sometimes their imagination is richer than what the technology is capable of delivering – though it’s clear that for other viewers whose first reaction to putting on the headset is ‘Wow!’ that there is pleasure and surprise.

Doing this research from the experience of people who identify as gay – predominantly but not exclusively gay men – was a deliberate choice to propose that generalisable knowledge could be created from minority experience. Despite its apparent openness to transformation, much immersive digital technology is developed from a heteronormative position, with assumptions about who is active, who is watched, who is subject and object. As dancer and dance tech pioneer Ghislaine Boddington commented: “A high proportion of VR content is male heterosexual porn.. […]Content creators need to think in a much more diverse way”. Of course all generalisations are open to challenge and in this instance, it was the female in the room – Tic – who was the most avid gamer. With gay men of different generations (in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s – pre and post-PREP generations,) of different different cultural origins, it wasn’t as if we approached the research from a single perspective. What might seduction mean to those of use more comfortable or at least more familiar with cruising or flirting online rather than in ‘real’ space [and in which particular places rather than abstracted ‘space’ – on a street, in a club, in a studio, in a classroom?]. While the perspectives we brought to bear on the research were neither homogenous nor exclusively ‘gay’, it was important to be in an environment where it was possible to bring our gay experiences into play, with sufficient trust and mutual understanding to be able to delve into the differences between our experiences too.

Doing this research from the experience of people who identify as gay – predominantly but not exclusively gay men – was a deliberate choice to propose that generalisable knowledge could be created from minority experience. Despite its apparent openness to transformation, much immersive digital technology is developed from a heteronormative position, with assumptions about who is active, who is watched, who is subject and object. As dancer and dance tech pioneer Ghislaine Boddington commented: “A high proportion of VR content is male heterosexual porn.. […]Content creators need to think in a much more diverse way”. Of course all generalisations are open to challenge and in this instance, it was the female in the room – Tic – who was the most avid gamer. With gay men of different generations (in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s – pre and post-PREP generations,) of different different cultural origins, it wasn’t as if we approached the research from a single perspective. What might seduction mean to those of use more comfortable or at least more familiar with cruising or flirting online rather than in ‘real’ space [and in which particular places rather than abstracted ‘space’ – on a street, in a club, in a studio, in a classroom?]. While the perspectives we brought to bear on the research were neither homogenous nor exclusively ‘gay’, it was important to be in an environment where it was possible to bring our gay experiences into play, with sufficient trust and mutual understanding to be able to delve into the differences between our experiences too.

Having just seen the film Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire which BFI describes as ‘a countermeasure to centuries of the male gaze in art, reaching out to other female artists and poets in its study of desire and creation’ , it’s clear that these questions of gaze, of seduction, of the brilliance and danger of being ‘on fire’, or ‘immersed’ are not exclusively male nor heterosexual. Working on this research has allowed an engagement with the intimate, the playful, the poetic, as well as the risky, the provocative and the uncertain. As well as continuing to develop our particular experience for audiences and participants, I think there’s scope for us to share this approach to immersive and augmented technologies with other makers, developers and technologists to help to shape a more inclusive, diverse and embodied approach to how these technologies evolve and in evolving, change us.

Having just seen the film Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire which BFI describes as ‘a countermeasure to centuries of the male gaze in art, reaching out to other female artists and poets in its study of desire and creation’ , it’s clear that these questions of gaze, of seduction, of the brilliance and danger of being ‘on fire’, or ‘immersed’ are not exclusively male nor heterosexual. Working on this research has allowed an engagement with the intimate, the playful, the poetic, as well as the risky, the provocative and the uncertain. As well as continuing to develop our particular experience for audiences and participants, I think there’s scope for us to share this approach to immersive and augmented technologies with other makers, developers and technologists to help to shape a more inclusive, diverse and embodied approach to how these technologies evolve and in evolving, change us.

Post a Comment