I hadn’t been at Glenstal Abbey since I was 14 and I cracked my cheekbone playing rugby for my Cistercian College Roscreal against the Glenstal school team. I’ve just spent two days this week participating in a workshop at the abbey that foregrounded my body again? The workshop had been advertised as focusing on Music, Mysticism, Religious Imagination and Ritual but by the time I got there, it had, with a generosity and openness that I admire in the Abbot Patrick Hederman, transformed into an exploration of the body and religion. Though there was a lot of thoughtful discussion, the workshop placed art – music, visual and choreographic – at the heart of expression.

It was a pleasure for me to arrive in the middle of day two and find myself in a singing session with Noirín Ní Riain and Micheál Ó Suilleabháin, connecting me to the first time I encountered them in the sevntieswhen they lived in Ring (where I grew up) and led the choir there. This was just the first of many powerful serendipities.

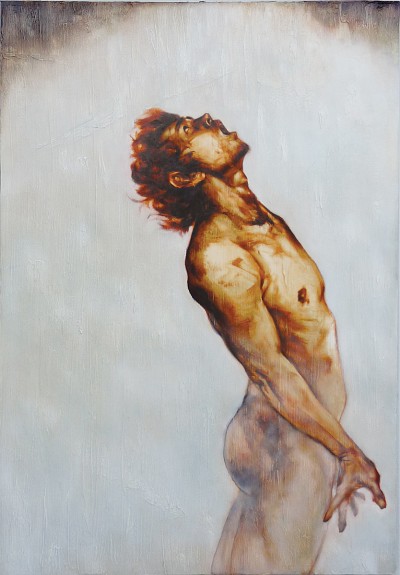

One of the novices at the monastery, Emmaus O’Herlihy, is an artist and with the encouragement of the Abbot he has produced an exhibition of striking paintings that

‘endeavors to bear witness to the challenging declaration of faith in a God made man, whose life, suffering, death and resurrection insists that our salvation rests in embracing Him in our human condition—not apart from, or in spite of it : In Tertullian’s lapidary phrase Caro Cardo Salutis (The flesh is the hinge of salvation’.

While I don’t have the confidence or perhaps the right form of faith to write in these terms, I was moved to tears seeing Emmaus’ paintings. They are depictions of the creation of Adam, of Saul’s conversion, of Christ risen and of the beloved disciple. And they are also images of male physicality, of human suffering and of desire. The holiness they seem to endorse is one that is inseparable from flesh, desire, beauty and suffering. I might not share with Emmaus a religious language to talk about the work but I feel a strong kinship between our artistic expression and its acknowledgement of the necessity of the body to understand the spiritual. I was amazed to see in his depiction of the Beloved Disciple the same open mouth, upturned face and receptive hand that features in Mo Mhórchoir Féin and in Tabernacle.

[/caption]

[/caption]

Fr Gregory, one of the abbey’s many theologians, spoke of the abbey as a refugee camp for those damaged by Irish Catholicism in recent years. Given that the Tabernacle was for the Jews, a kind of tent into which God came to communicate with them, I am already a fan to the kind of mobile nomadism that the refugee camp implies, even if there is a trauma that brings the refugees together. But I also see Glenstall as a laboratory, a place of exploration and possibility where a new articulation of possibilities might emerge. It feels like a place where spirit, body and mind might all be honoured.

It’s not easy to write about this. It feels exposing and embarrassing and not at all cool. But in the wake of the Cloyne report which revives the pain of betrayal felt by many in Ireland in relation to the Catholic Church, openness, even about what is not cool, not comfortable, not dignified feels like the only ethical strategy for going on.

Post a Comment