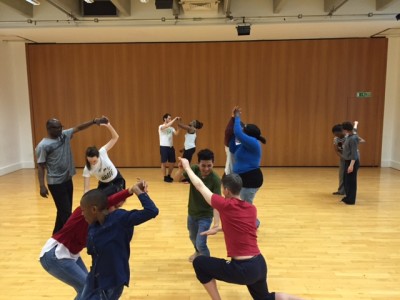

Photo Ste Murray

Each phase of rehearsal has been important, but I knew that this past two weeks would be especially significant. I was confident that we had the material of the piece but I needed to find out its shape, to let its contours reveal itself as we assembled, disassembled and reassembled material and tested it under the influences of music, set and costume.

Photo Ste Murray

It was essential to have Dance Ireland’s Creation Studio to make that process possible. In the past, I’ve rehearsed in spaces where we needed to clear away our belongings each evening. That necessity discourages bolder scenic experiments that you’d want to leave in place over a rehearsal period. And I loved arriving into the studio on my own early each morning and feeling the world that we were building already in place, waiting for the dancers to inhabit it.

Photo Ste Murray

One thing that became clear as soon as we started to work with the design elements that Ciaran had brought in to the room was that we would need to continue working with those elements in the final phase of rehearsal that remains for us just before the premiere at The Place next month. Though it’s been inconvenient and an additional expense to find alternative rehearsal space to what had been provided by generously The Place (their space wouldn’t allow us to work with the design elements), I was pleased to be discovering what the piece demanded of us. It was letting us know what its requirements would be and how we would need to respond to them.

Photo Ste Murray

Similarly, it became clear to me that the piece could have a distinct name now. Butterflies and Bones is a title that Matthew suggested some time ago and which appealed to me immediately. However, I wasn’t sure at the time how the work would grow. By last week, I could see that Butterflies and Bones was ideal, bringing together the shimmer and shade of Casement’s life and of the lives of most people I know. He collected butterflies in the Amazon while documenting the human rights abuses against the local people there. One mind could, maybe had to, find beauty alongside the tragedy.

Photo Ste Murray

The validity of the new title is an inconvenient realisation. We’ve already gone to print with the existing title of The Casement Project for this stage work and for the most part, we’ll have to stick with it – for the London shows at least. But because I choreograph by enquiry rather than fiat, I’ve had to be patient and trust we’ve built in sufficient flexibility to cope with these later discoveries. It’s also how I work with the performers and creative team: keeping an open structure in the creation until what is necessary reveals itself, and leaving open to change that which isn’t necessary today. I sometimes (often?) feel guilty that I don’t have more definitive answers for the performers and for the creative team, that I don’t just say, ‘it’s like this and this and this. Step ball change, Beyoncé, Beyoncé and hold!’. But the not knowing on my part is also what keeps me interested in choreography. I’m learning from the dancers, from the creative team and from the work itself. It confounds my expectations, points out that what I thought would happen isn’t appropriate, and offers delightful compensations alongside the humbling lessons.

Photo Ste Murray

After rehearsals at The Place, I had two related questions, in response to feedback from people who saw our work-in-progress: what would I tell people about Casement and how much text would be in the work? As someone who wants to use Casement as a way to reflect on contemporary questions of belonging and becoming, I don’t want to make the dance biographical. Having seen Arnold Thomas Fanning’s Mc Kenna’s Fort – an excellent one-man show based on Casement’s life and filled with historical detail – it occurred to me that most people think of historical facts as a list of dates, names and places that can be written down and tabulated. But these facts don’t communicate what the water felt like when Casement swam in Amazon, what a uniform felt like when he accepted a knighthood, what it was to experience the thrill of cruising in Las Palmas, or the sensation of playing billiards with an old friend with whom he hoped to have sex within the hour. These sensations are physical facts that bodies retain and that bodies communicate from one to another. These embodied facts (physical, neurological, endocrinal, muscular, energetic) shape cultures and get passed on from generation to generation. In dancing with this legacy, especially through the articulate, intelligent bodies of these gifted performers, I think we are engaging with our own personal and cultural histories, processing historical facts that are most often neglected in considerations of what counts as History.

Photo Ste Murray

As for text, in the end there is more of it than I had expected, though it’s not text that defines or explains the movement. It is allusive and associative. It dances. For those that are interested in biography, I can point to the wealth of research that has informed the work and to the symposia engage with Casement in an academic way. The Casement Project is designed to welcome those approaches too.

Photo Ste Murray

At the end of these two weeks, I can recognise what Butterflies and Bones has become. Thanks to feedback from people who came to see our showing on the final day, I have refinements and clarification to think about, and the final design elements that will add new energies. I’m excited to meet them all.