Jeffrey Dudgeon (photo Pari Naderi)

HOSPITABLE BODIES: THE CASEMENT SYMPOSIUM

Roger Casement in 1916

Friday 3 June 2016

British Library

Jeffrey Dudgeon

I am opening today’s session and have therefore to give you a crash course in the Casement diary controversy, and indicate where the ‘Hospitable Bodies’ are buried.

If I offend I apologise. The clue is in our title, but any offence taken may be of an unexpected kind.

I have to caution, there is an Irish view and a British view of Casement, contemporary and modern, as well as a gay and an Ulster one.

The contemporary British one was that the country was at war; Casement was a former diplomat and thus a traitor, also ‘a moral degenerate addicted to unmentionable practices,’ as the top Home Office lawyer, Sir Ernley Blackwell, told the Cabinet.

Those points would not be made now in London. Indeed there has been a recent call in the Irish Independent by Martina Devlin for Britain to apologise for its actions and attitudes, a demand which may gather pace and come to the capital.

The popular Irish view today is that Casement is a humanitarian hero brought down by British securocrats and homophobes.

A cheerful variation of this, common to most Irish writers, artists and commentators, is: Yes he was gay. Yes he wrote the diaries. Ireland can take it. This is the Ireland of the Equal Marriage referendum. Now move on.

The older Irish view, when it was declared (and leaders like Eamon de Valera advised people to keep clear of the subject) was that Casement was an Irish patriot and thus could not be a pervert, while the British had plainly used forged diaries to ruin his reputation.

Today, for that Irish minority, the diaries are still forged. But they no longer argue that they portray the author as a homosexual, rather, now, a paedophile. And for the same reason, Casement, the Irish revolutionary, who became a Catholic on the morning of his execution could not have written them or be that author.

Those who believed in forgery saw the British as devils incarnate while the charge of homosexuality was without parallel, in their view, being something utterly indecent and immoral. Casement, to many, took on the aura of a martyr saint, almost because of the accusation. That view lives on, in different forms, today.

This does create the danger, if the forgery theorists are proven wrong, that they have called their hero the worst thing in today’s world – a paedophile, someone who groomed boys.

Anti-revisionists who hold to the separatist position of Casement (and his colleagues in the Easter Rising) will not move on. Cannot move on. And they are gathering strength, as we speak – not unrelated to the centenary celebrations. Many are out of the US.

I quote here a description of me by Angus Mitchell, my publishing rival and the primary exponent of the forgery theory, to indicate the depth of his belief and the level of disagreement: “Jeff Dudgeon uses the Black Diaries to update the queer geographies of Ulster and to re-imagine Northern Protestant nationalism as some high camp drama driven by a cabal of queer crusaders.”

Casement is for many the key figure who wrote and articulated the anti-imperialist position, alongside Connolly – and they both acted it out, unto death. It is coherent and can convince. The First World War was such an unmitigated disaster for millions that the actions of one militarist are rarely worse than another’s.

But Casement had actually come to appreciate German imperialism. As I wrote: “He openly expressed an appreciation for Germany; one ironically shared by some of his Ulster opponents – for the same and other reasons. They all viewed united Germany as a fresh power untainted by cynicism or a long history. The problem, unrecognised by Casement, was that a rapidly developing power is only able to expand its frontiers through a belief in its own virtues and superiority. Else why bother. And new world powers without a history, and worse, untouched by experience, once in an expansionist mode, are not going to operate a humanitarian regime.”

The view on Casement seems to be cleanly and neatly split between the state and the cultural.

President Higgins, as he can, however came closest to breaking official ranks at Banna Strand last April by pointing out he landed to stop the Rising, along with Daniel Julien Bailey (or Beverley) who is no longer being written out of the history. His later story like those of John McGoey and Adler Christensen is one I deal with in my second edition.

Casement was also Anglophobic, which is less agreeable. As happens with the British left, unwisely, too many hate their own country much more than they love the working class. Casement hated his. Indeed he switched nationality which is at least honest.

Foolishly, anti-revisionist historians hold to the conspiracy theories around the diaries and are thus doomed to political disappointment because forgery is not a credible option. They rely too on the Irish forgetting, or failing to realise they (like the British) have interests, and must make messy compromises.

Angus Mitchell crosses over with his most recent remarks: The conjured-up “Black Diaries replace Casement’s clear, accusatory voice with ambiguity, exaggeration, innuendo and plenty of casual sex.”

The gay view would not be that Casement was an icon, or necessarily a hero, but that he was one of us, whose sexuality brought him to the gallows.

(I would demur, in so far as Casement was doomed to die – unless and until London’s mood changed, as it did by late 1916. Remember the Battle of the Somme was in July a few weeks before the execution, with thousands of Ulster Irish dead.)

He was however one of us, even if he showed no interest in trying to change the world, where homosexuals or lesbians were concerned.

It is not true as Angus Mitchell says in his recent GCN ‘Black Stain’ article[1] that his recognition as an “advocate of human rights is dwarfed by those who claim him predominantly as a sexual liberator”. In contrast, and I quote one, Tina O’Toole, some “queer scholars see his sexual identity as intrinsic to his humanitarian impulse.”

Casement lived a gay life to the full. It is not yet a crime to put the sex back into homosexual, even though some have accused me of prurience, because I, not only published the more expansive and erotic 1911 diary, but had the temerity to explain some of the sexual aspects. (It had been suppressed until 2002, and mine remains the only version.) The sceptics miss the human side of people, and don’t credit the interesting, often contradictory aspects, of lives lived.

The Ulster Protestant, or Unionist, view would, as always, be, both unyielding and, as it has to be, conservative: it is an existential struggle about survival. Casement threatened that survival and still does. Ethnic disputes are never resolved but can be subsumed, as those in Ireland are being now. For how long remains an open question.

Unionists however will not warm to Casement, even as a humanitarian. They will ploddingly remind you that the Foreign Office commissioned both of Casement’s reports on rubber slavery in the Congo and along the Amazon in Peru where it was more vicious and indeed approached genocide.

History will be written from these varying points of view but there is already a synthesis or majority view, one that will drive the future.

I say that whosoever gets the facts right and marshals the evidence, as opposed to making assertions, or simply lawyering, as so many diary deniers do, will produce the best and the most convincing history.

Can any history be objective? I have tried to be honest, and fair, and reasonable. But conspiracy theory and lawyering are outwith acceptable historiography. The verdict of history is not to be likened to judgments in a court of law. Nothing will ever be so absolute but one can sift the evidence and make reasonable deductions.

As Ulster Unionists are the most unloved and disrespected community in the West, or perhaps the second, except by a kindly section of southern Irish society, what I say will not make us any more loved or convince many nationalists, but I can live with that badge of honour.

Are Unionists ever sexy? Are they just gloomy, backward, and with no culture – without hope and without a future?

I think first of my hero Harford Montgomery Hyde, author of that unequalled history of homosexuality in these islands, ‘The Other Love’. An Ulster Unionist MP in the 1950s (for North Belfast) who majored in the House of Commons on homosexual law reform – when hardly any dared – and on Oscar Wilde and Roger Casement.

By the way, two of the three gays on Belfast City Council are Unionists. Things advance even if Northern Ireland is a little behind, closer in proportion to the 40% in the south who voted against gay marriage. But if London insists on devolution, its advocates must accept that the locals have the right not to be progressive, in their terms. At least, I and others have ensured we will never go backwards.

Who knew Casement was gay, and I use that word carefully. He was living in an era when there was no word to describe what his state of being, his sexual orientation was? I have reasonably indicated – but the evidence is slim – that Sidney Parry, Alice Stopford Green, George Gavan Duffy knew, and probably his cousin Gertrude Parry (at least several playwrights have written accordingly).

To those who would argue that there is little or no eyewitness evidence of Casement’s homosexual activities, I quote the remark made to me on the steps of the Royal Irish Academy at the 2000 symposium, “When I came out, no one was more surprised than my wife.”

And to those who accept the diaries as genuine but cannot credit the extent of the sexual content, I can only point to what was said to me last night at the Irish Embassy reception by a prominent lawyer. “Only 300 yards from here, one night in Hyde Park, as a young man I was arrested and taken to court doing what Casement did, and as often.”

Casement never defined his status on the three occasions in his diaries that he remarked on the subject. Only the phase “terrible disease” was written in relation to the suicide of popular General Hector Macdonald because of his activities with Portuguese boys on a train in Ceylon.

‘Disease’ was a term used by reformers in the progressive medicalisation phase to get away from the criminal (bugger) and religious (sodomite) phrasing. The word homosexual which was coined in the mid-19th century only entered standard and official use between the wars.

Yet his diaries are the most concentrated and frank, if terse, exposition of a gay male lifestyle ever put on paper before the 1920s. As such, they are a social document of great interest, particularly to other gay men who come into the world without a history. The only historical record of our lives before then was the criminal record.

Why are the diaries authentic? Firstly because they give you that impression. They look real. They almost smell real over their 1,000 daily entries. And the more you know Roger Casement, the more authentic they obviously are, unless you are a career nitpicker or a republican lawyer.

The Irish author, Frank O’Connor, wrote of Casement that “the man was a maniac for scribbling.” Another Casement biographer, Roger Sawyer, noted his “compulsion” to write, an urge that seems to have been at least as strong as his sexual desires: “He was capable of writing no fewer than three versions of the same day’s events, working at his largely self-imposed task long into the night, and into the early hours of the following day.”

That is what the diaries tell, those four that remain due to falling into London’s hand after his capture. The others were destroyed, along with some political and most of Casement’s personal correspondence in 1915. They were stored in three cases at the house of FJ Bigger. George Gavan Duffy, later his solicitor at his 1916 trial, and Art O’Brien being asked to do the needful as I have recently discovered.

I mention here a recent article by Paul Hyde in Breac, a Notre Dame University interweb publication which lists the 20 unanswered questions that he says have the diaries failing the test of authenticity: the first three being how, when, and by whom were they found – a Mr WP Germain of Ebury Street brought them into Scotland Yard on 25 April 1916. If Mr Hyde had read my book he would find his questions answered, but I know they would not satisfy him.

That 700-page book with all the diaries, except the German one, was published in 2002; the second paperback and Kindle edition came out this centenary year. The German Diary is presently in production.

I have to quote from the playwright Arnold Thomas Fanning in the Irish Times in April: “This extraordinary book is a minute dissection and decoding of the Black Diaries, and the fullest and most thorough exploration of Casement’s private life as a gay man. As such, it is essential reading to get the full picture of who Casement was and how he thought.”

I don’t complain though I will mention it. I am excluded, most recently from the 2013 Tralee conference proceedings in Breac and those published after the 2000 Royal Irish Academy Symposium. In both conferences where I spoke, my submitted contribution was not printed. They were wordlessly omitted. Angus Mitchell however has monopolised certain ‘national’ outlets and that’s to be expected. Yet he attacks the academic historic community feeling he has not been admitted to it. Nor can he be, probably, as he uses different, post-modern, techniques.

People ask me innocently how did I come to Casement? I read the Black Diaries in the 1970s having bought Singleton Gates’s book, but only after the earlier works by René MacColl and Brian Inglis. I innocently thought at that time the authenticity debate was over but being gay and an avid reader on the subject from the 1960s, be it James Baldwin or John Rechy I was fascinated by this gay Irishman and of course the controversy attracted.

When the two disputing versions of the 1910 diary, by Roger Sawyer and Angus Mitchell, were published in 1997 my interest was re-whetted and has been ever since. This was the first fightback by the forgery school for 40 years. Angus Mitchell has been the motor since.

There are many similarities between myself and Casement which probably drew me to the subject, but there are, and certainly came to be, huge differences.

We are both Ulster Protestants – or was he? He was born in Dublin but brought up in London, in difficult, déclassé, circumstances (e.g. his court appearance for theft in London as a child), orphaned and sent to Ballymena at the age of 12 – to the heartland of the Ulster Scots Presbyterians. (Some were liberals but that was a dying tradition).

It must have been seriously difficult for a gay, teenager, a blow-in, an Anglican with an English accent, but his Ballymena teachers were the best, even if he pretended otherwise and he excelled academically. His better-off relatives however warred over his future and did not club together to pay for a university education. He then went to his uncle in Liverpool, to the shipping trade, and ultimately the consular service.

We were both radicals from something of a parental influence, and probably had a number of the resentments common to many LGBT people.

We were both therefore outsiders and campaigners. He was assiduous, industrious and dogged, far beyond my mode. And braver.

I was a political gay, where he was a sexual gay, he being gay in deed but not in words.

Neither of us are guilty Prods, as he went over entirely to separatism having been a teenage Parnellite. I returned early to my ethnicity as a war enveloped my city and life. One he had a part in starting. I am not a hater of the English, far from it.

So I am uniquely qualified to talk about Casement, and for those same reasons can be written off as prejudiced.

Am I able to be objective given my two positions of Unionist and gay, or is that too much for antagonists? If they can’t get me on one, then the other will do. But I can tell when and where the Emperor is naked or at least in threadbare clothes. I can say the unsayable. I am also instinctively antagonistic to conspiracy theories, be they relating to JFK, Kincora or Casement.

However the dispute or controversy can never end as it comes down eventually to belief. This is welcome news for my heirs as royalties from my 2nd and Kindle editions will continue to accrue, long after I’m gone.

Angus Mitchell, again in his Black Stain article in GCN, calls for “the question of Casement’s sexuality to be decoupled from the textual” adding, “This requires hard and rigorous questions concerning the Black Diaries to be asked, and answered, about provenance, motive and probability. It also requires us to engage with the murky aspects of the ‘Dark State’ and the long conflict in both Britain and Ireland against republicanism.”

Partition is the ghost at the feast, the unmentioned subject in Casement discussions. His failure in that department was boundless yet goes undiscussed. But Angus Mitchell, despite the above will not engage on that terrain, any more than the diary deniers will fight on the facts.

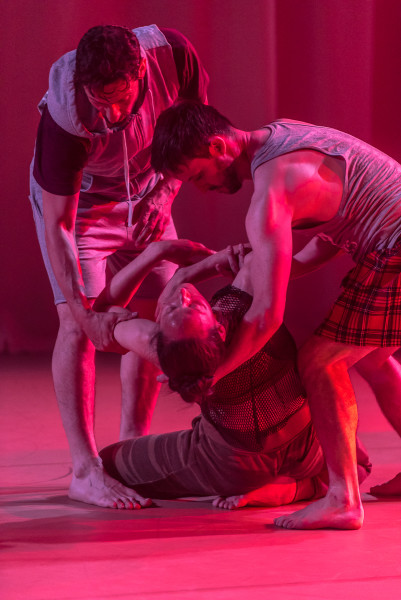

Jeffrey Dudgeon, Caitriona Crowe and Gerry Kearns (Photo Pari Naderi)

[1] Gay Community News (GCN), pp. 20-22, Dublin March 2016. http://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk//launch.aspx?eid=91c83c21-2e2c-44f6-ba5a-f77a3f13afaf