On 4 April, the Arts Council presented a symposium to reflect on its ART:2016 programme. Curated by Róise Goan, it asked: What does it mean for the State to support artists in examining a key historical moment that is future focused? What is the impact on the artist and their work? What is the impact on the community that engages with that work?

I was moved to see and hear the work of the other artists involved in the programme, and especially to feel the strength of the values that drive them. You can see more of what happened on the day on the Arts Council’s Facebook page where the event was live streamed. Here’s what I said (more or less)…

Buíochas mór le Róise agus leis an gComhairle Ealaíon as ucht an deis labhartha libh inniu. I’m taking this opportunity to celebrate what we’ve achieved in The Casement Project. It’s not something I’ve often done on previous projects and I want to recognise what’s different this time. This time we were able to allocate enough resources to finish the project well, to pay people for the time it takes to reflect, discuss and write reports, reports that aren’t just fulfilling the obligations to our funders, but that generate learning for me, for us, for anyone else who might value some insight into what we did and how we’d do it next time. And there is a claim in this taking time to reflect, to evaluate, to learn for next time – because it boldly imagines a next time. And for an artist who has no guarantee that he will ever be funded again, that imagining of a next time and of a future in which a next time would be possible, is one of my best creations (with all the physical, intellectual and emotional energy creation entails). So in starting today with a celebration and commemoration of what The Casement Project has been, I hope you can see that the looking back is a strategic contemporary intervention with a changed future in mind..

The Casement Project, was a choreography of bodies and ideas that took place across multiple platforms and national boundaries. In the context of our centenary commemorations of the Easter Rising, but also of the First World War (and the sometimes fraught interrelation between them), the work danced with the queer and complex body of Roger Casement – British knight, Irish rebel and international humanitarian. [And of course, Casement was imprisoned in the Tower of London that has featured in Deborah Shaw’s wonderful description of the Poppy project.]

The choreography was designed to reflect on the relationship between nationalism and the body, to ask the questions: Who gets to be in the national body? Whose bodies represent the nation? What bodies are empowered or excluded? How might the national body move? How permeable are its borders?

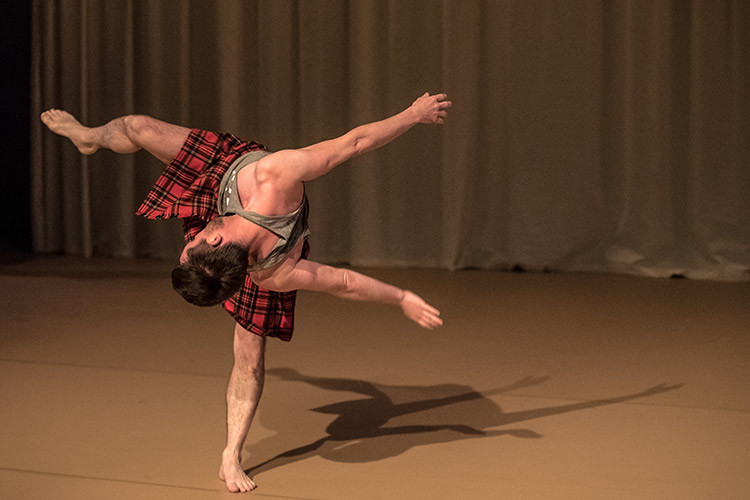

Behind the project was a belief that despite our verbal skills, our linguistic creativity, that many Irish people are not fluent with or about bodies. And in the past hundred years, our individual and collective bodies have suffered and continue to suffer as a result of that lack of corporeal articulacy. Though Casement is renowned for his words – his reports denouncing human rights abuses in the Congo and in the Amazon, his poems, his letters, his diaries – it is his body, what it did and where it went, both in life and in death, that has always been most troublingly political. His always mobile body, always in transit, responded bodily to the bodies he desired. He also read the marks of exploitative colonialism and capitalism on the bodies of indigenous people in the Congo and the Amazon, and ultimately linked those bodies with the malnourished bodies of children in the west of Ireland under British rule. After death, his own body, intimately probed to examine his sexual history, was discussed at the British Cabinet, and the resting place of his bones remained a point of political dispute between the British and Irish governments for a further 50 years. When, in 2016, politicians have celebrated the artists who authored the Easter Rising, I think they usually have poets and perhaps a musician in mind. In mobilizing Casement and his complex body, I wanted to make sure that choreography of the Rising and of the State it set in motion could be visible; that the value of dance as a art form that knows about the formation of individual and collective bodies could be applied as a way to re-imagine that foundational choreography. I also wanted to use Casement’s international profile as a way to remind us that we can’t think about the flourishing of a particular national body without attending to global questions of justice and to the kind of inclusive, dynamic and permeable collective body such a global perspective might necessitate.

All of this is pretty much what I said in my Open Call application. And I’m still saying it because just as puppies aren’t just for Christmas, Casement, or more properly a better understanding and experience of a diversity of bodies, isn’t just for Easter or even for 2016. And I’d like to talk a bit more about in a moment.

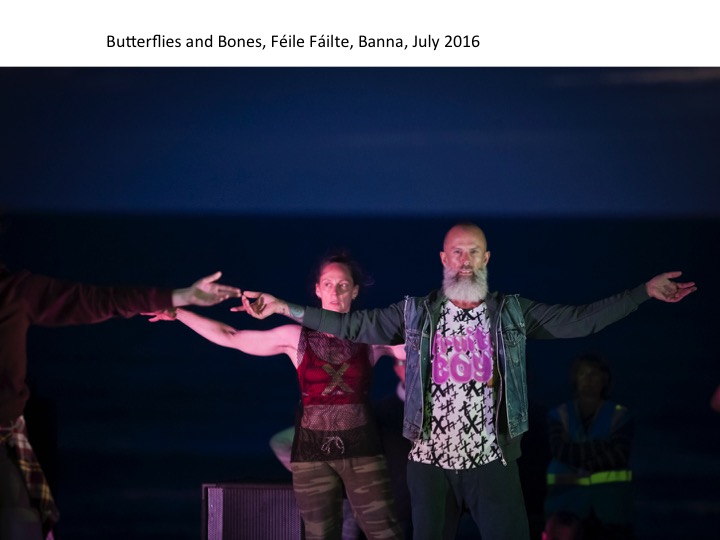

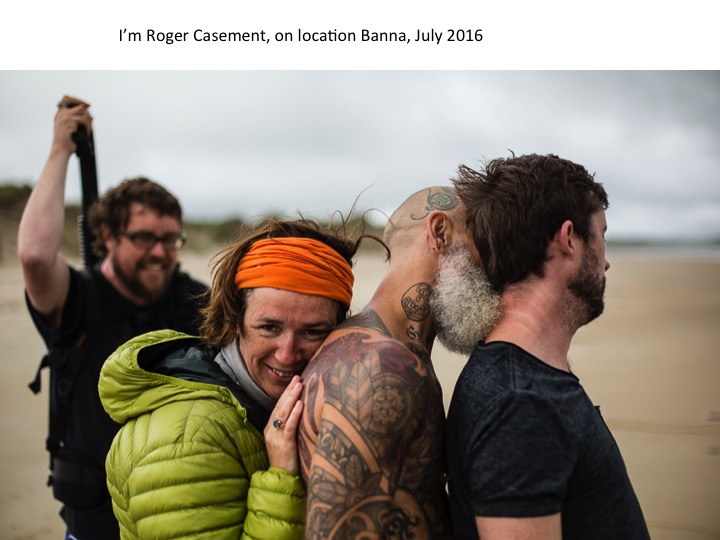

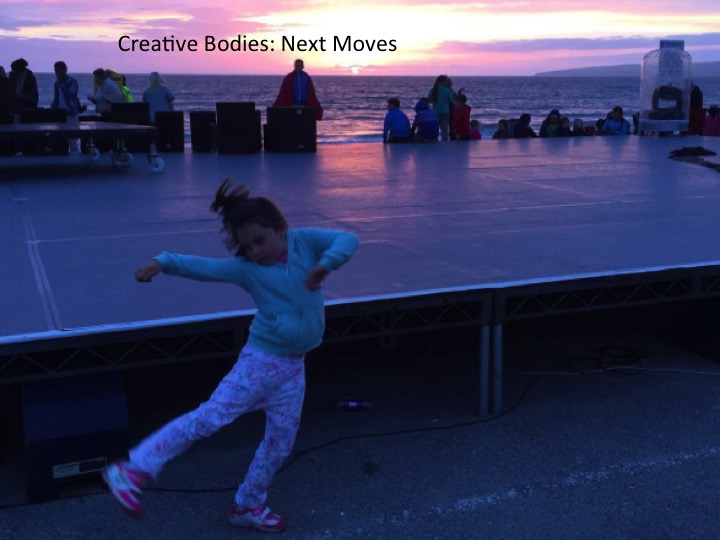

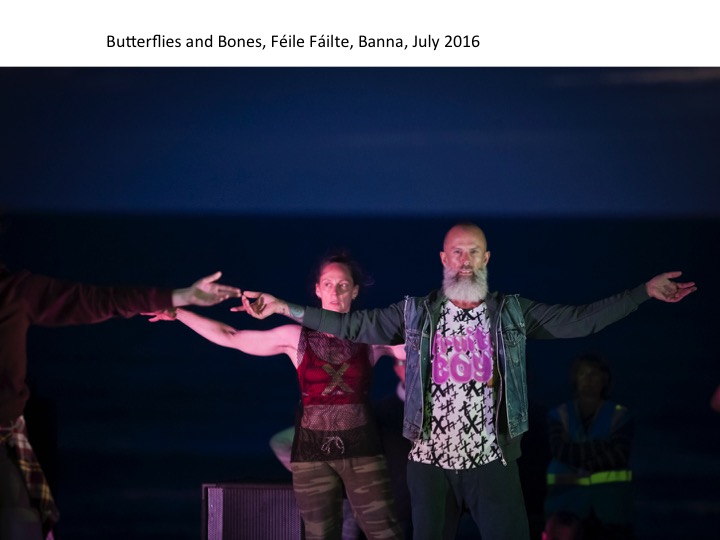

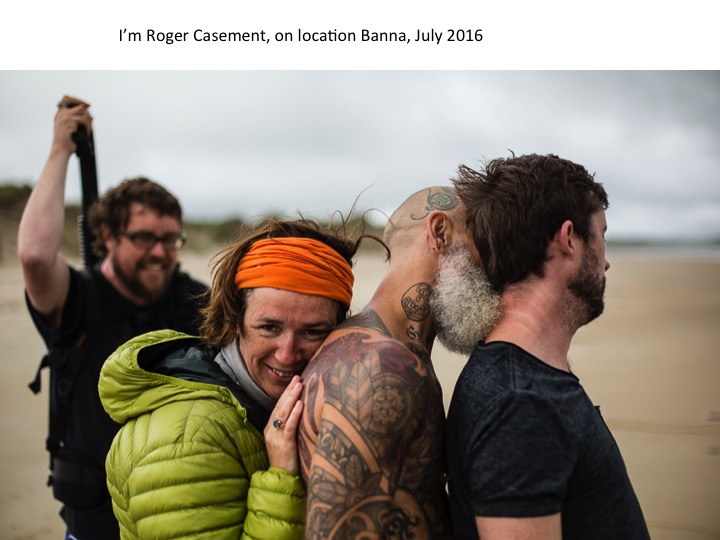

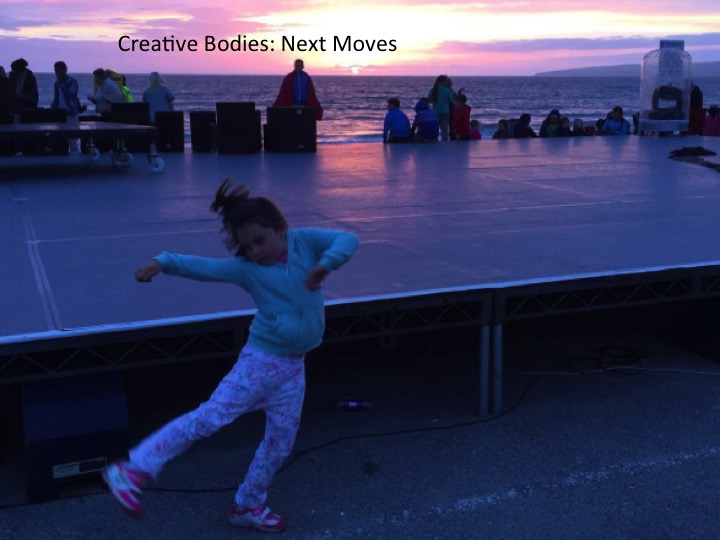

Over the past year almost 90,000 people engaged with The Casement Project in various ways, joining in, seeing us on stage, on screen, participating in conversations, dancing on the beach. We started the year with the Bodies Politic symposium at Maynooth where we invited artists, academics and activists working with the body and commemoration to share common concerns. And I will co-edit this year a book of essays we commissioned from some of the contributors to the event. We had a second symposium in the British Library in London before opening our stage show, Butterflies and Bones at The Place Theatre, across the road. That London premiere was always important for me as a way to expand the context of the 2016 commemorations, to extend a narrow conception of what a national body might be (both in Ireland and in a Brexit-inclined UK). As part of the 1418NOW commissioning strand in the UK, commemorating WW1, as well as part of ART:2016 programme, The Casement Project was designed as a choreography of partnerships, contexts, and histories as well as a choreography of bodies on stages. My mission is to see and work with those macro-choreographies through the micro-choreographies we explore in the studio. Following Casement’s lead we presented Butterflies and Bones in London, Dusseldorf, Belfast and Dublin, as well as on the beach in Banna as part of our day of dance to welcome the stranger. Over 2000 people came to Féile Fáilte on the beach where Casement had come ashore 100 years before. We also filmed our I’m Roger Casement short film there and it was shown on RTÉ at the start of this year to 83,000 people, spilling beyond the 2016 container in a way that I hope will continue with further broadcasts and screenings. We had a club night, our Wake for Roger Casement, at Kilkenny Arts Festival. Alongside those public events, we had opportunities for creative engagement with all kinds of people in open rehearsals, lecture demonstrations and in workshops with LGBT refugees and asylum seekers (that are still going on as an important legacy of the project). Too often, people make great work that no one hears about and so I wanted to integrate communication into the artistic strategy of The Casement Project, not as an add-on but as part of the material and the medium of the project. Annette Nugent, who was communications consultant for The Casement Project, will talk later about the practicalities of choreographing the way the project was manifest in print, broadcast and digital media. She and Kate O’Sullivan brought particular creative skills and expertise to the project, alongside like Ciaran O’Melia, Alma Kelliher, Dearbhla Walsh, Brenda Morrisey, Lian Bell(when she had so much else going on with Waking the Feminists), Cian O’Brien, Marcus Costello, Aaron Kennedy and the dancers, Mikel Aristegui, Bernadette Iglich, Philip Connaughton, Liv O’Donoghue, Matthew Morris and Theo Clinkard. And I want to acknowledge that part of the impact of the whole project comes from having paid attention to how it has lived and will live in various media.

So nearly 90,000 people saw or participated in The Casement Project. I’m stressing this for myself, as much as for you, but while 90,000 is an encouraging number, even more encouraging was the care and feedback that one individual gave at Féile Failte during the summer.

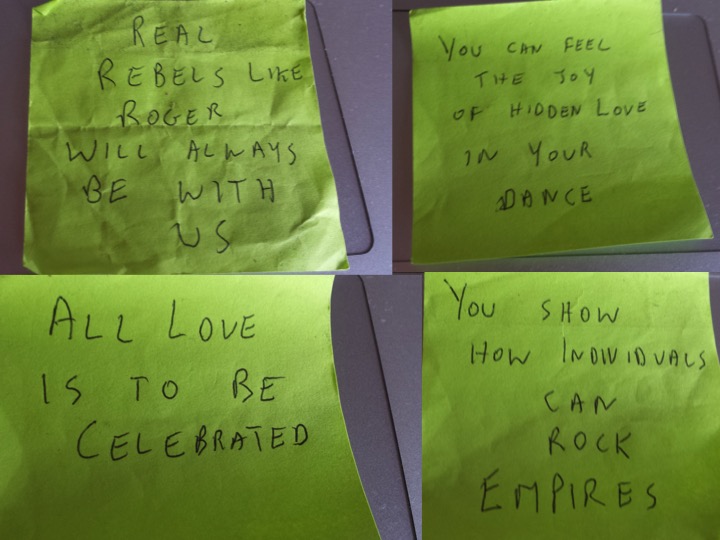

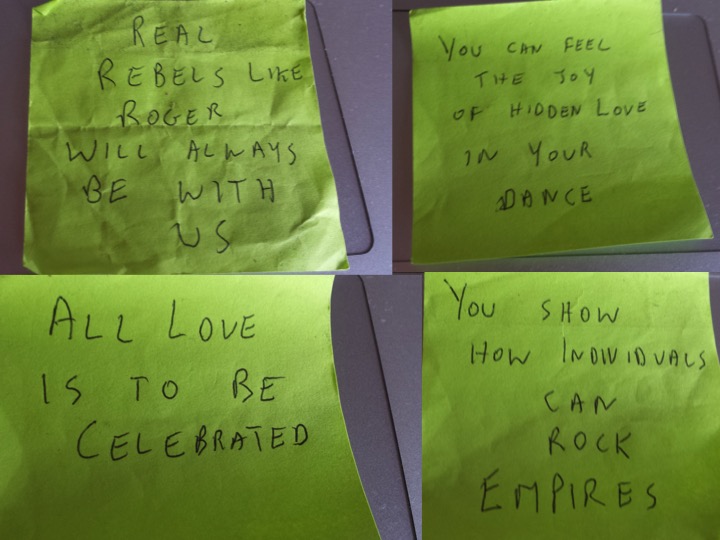

The night before the event, when the amazing technical team had put everything in place and we’d rehearsed until late on the beach at Banna, a man arrived over the dunes with a satchel of tea and coffee for us. He’d seen that we were working late and responded with this kindness of refreshments. Perhaps in his sixties, he chatted with the dancers and me about what we were doing, but I didn’t find our much about him. I don’t even know his name. I only appreciated the welcome and care he showed to strangers, that seemed already a model of what I hoped our Féile Fáilte would be. After the event next day, after dancing, and pyrotechnics, and the disco, when I was exhilarated but exhausted, as people were leaving the beach, the man came to us again this time with snacks, and tea and whiskey. He gave me a set of post-it notes with his response to the day. He had written: All love is to be celebrated. You show how individuals can rock empires. You can feel the joy of hidden love in your dance. The mighty powers tremble before individual universal desires. Rebels like Roger will always be with us.

If I am keen for many people to see my work, it is not with the expectation that everyone will like it. (I was taken to task by an audience member at a talk in Kilkenny Arts Festival for giving credence to the ‘lie’ that Casement had sex with men. And following reports in local press and radio about the performance of Butterflies and Bones at Féile Fálite, a local councillor in Cork who hadn’t been there decried the work as disrespectful to the Casement family and to the audience.) But if we didn’t take the risk to claim public space, on a beach, on the internet, or on television, for a kind of work and a kind of world we want to embody, how would people like that man find us

I’m tired and that makes me anxious because I worry that my existence as an artist and my subsistence as a human being depends on my being active and productive. The artist in me knows that I need some fallow time to listen to what I should do next and I wish I’d had the courage to build that fallow time into this project and its funding, since we all know that the fallow time is an important time in the productive cycle. But in retrospect there are a number of things we left out of the budget. I’ve called myself an independent artist for a long time and I’ve valued the flexibility and mobility it’s allowed me. But it is a fiction, one that’s encouraged by a neo-liberal ideology that has promises self-employed autonomy, and delivers precarity instead. I’m not independent. I’m an inter-dependent artist, reliant on and contributing to networks of support, alliances of solidarity and encouragement that enable me to make work with others. The Casement Project depended on the skills, creativity and good will of a small team that we assembled for the project. We hadn’t all worked together on a single project before, though we all knew each other and shared values. We jumped straight into delivering this major project. We had to. There was so much to do. What we didn’t do was invest time and resources into figuring out how we would work together. That would have seemed like a luxury, an unnecessary expense, and of course because it was an amazingly competent and generous team of people we were fine. However, in being fine, we were drawing on existing capital, not investing and that’s not sustainable in the long term. And we pushed on when there might have been moments of reflection that would have helped us make the work even better. What we budgeted for was delivering, but the reality is that delivering is only part of life-cycle that makes something like The Casement Project possible. And maybe part of the tiredness I’m feeling is that we only invested in delivery and not so much in preparation and recovery.

Some of the team on a recce to Banna

The other impact of not investing in building the temporary organisation that The Casement Project turned out to be is that leaping straight into delivery meant there was no time to take a risk on new, inexperienced people. I worked with a team of highly experienced, talented people, mostly people I already knew. That was great, but in the long run, its not good for me or for the sector since it deprives people who are less experienced of the opportunity to work on a project like this and it deprives me of the chance to work with them. It’s not good for diversity. In talking about investing in building a team, I’m not imagining that I want to set up a permanent company. But to realise projects of this scale, a team is essential and one of the things I’d encourage us and the Arts Council to think about is resourcing the structures of support that enable work outside the companies to happen. Project Art Centre was the invaluable anchor of support for me, and has been for many years, but it still required a dedicated Casement Project team to work with that support structure.

One of the other questions I’m left with after this amazing opportunity is what I’m supposed to do now with this experience of and appetite for working at scale. The Open Call asked us to be ambitious and offered unprecedented resources to support that ambition. Given that the upper limit for a dance project award is €50,000 (with a prioritisation of projects that can squeeze into that budget a broad range of touring alongside the creation and presentation) the opportunity that the Open Call represented was huge, more for a dance project than perhaps for a theatre project where the upper limit for production is €150,000 and where that production might also have benefited from previous development money not available to dance. I didn’t have to think differently to imagine a project that could take advantage of the resources of the Open Call award. I’ve always been trying to make work in the multi-dimensional way I have in The Casement Project. But on smaller budgets, I could only manage one dimension at a time, for a short period of time, without the communication support that makes an impact that in turns supports the further life of the work. The Open Call resources allowed The Casement Project to exist over a long period of time, and by existing over that time frame, to build momentum, impact and engagement. It has also been the case that resources have attracted resources with additional opportunities coming to us because of the Arts Council’s anchor investment.

So what am I supposed to do with this kindled and exercised ambition now? Having shown what dance can do when it’s resourced to succeed, do I settle for a diminished vision?

My answer, for the moment, is definitely not. I’ve heard myself talk endlessly about the need for greater fluency with and about bodies and sometimes wondered whether it’s time to move on. But just when you think we’ve made progress and outgrown restrictive legacies, the neglect of bodies like those of the babies buried in Tuam, or of those that live the penal choreographies of social and spatial exclusion in direct provision, the denial of bodily autonomy to a majority of our population all remind me that there is work to do. So in the spirit of Future Retrospection, I want to imagine a 2023 in which we will have commemorated the independence of the Irish national body by celebrating the confident freedom of a diversity of Irish bodies, autonomous but interdependent, recognising that individual flourishing depends on the flourishing of many others. I imagine that this celebration of Creative Bodies will have had artistic self-expression at its heart. It will not have been a keep fit programme, We will have built on the knowledge of dance as an artform that knows about how bodies are developed and explores what they could be. It presents different possibilities for how bodies come together and offers to society new choreographies for our lives together. We will have built on the knowledge of dance, and of other art forms that foreground embodiment. We will have built solidarities between artists, policy makers, scientists, sportspeople, educators and technologists, because it’s going to take a shared knowledge to make the kind of transformation that’s needed here to liberate a resource that’s been contained for too long.

So this is what I’ll continue to work on. I hope to see you in the dance.

photo by Kate Heffernan

Lian Bell, our brilliant Project Manager for The Casement Project but even more brilliant Waking the Feminists activist and leader

Annette Nugent (Communication Consultant for The Casement Project) with Kris Nelson, Eugene Downes and Tom Creed

Áine Philips, Future Histories, ART:2016

Fearghus Ó Conchúir and Karen Downey (Project Manager, ART:2016)