The second week at The Place was different from the first in many respects. We rehearsed in a variety of studios instead of the same large one; we had 5 dancers rather than 6; there were numerous visitors – Sarah Browne, Niamh O’Donnell and Tom from Project Arts Centre, Iarla Ó Lionáird, and photographer Pari Naderi. All of these changes had an impact on the way we worked and on the information we had to process.

As I reflect on the two weeks I still don’t know how the piece will evolve when we resume in May in Dublin but I know there is something there.

After Manuel‘s surprise at not seeing overt religious imagery, I spent last Sunday at the National Gallery buying reference books to share with the dancers. I had to realise that though I wasn’t bringing that imagery directly into the studio I was already carrying it in my own memory bank and that I needed to give the dancers access to the images even if we disperse them and reimagine them. The point for me is that that iconography informs our daily lives. In love, in calamity we recognise ourselves in those attitudes of religious imagery. Every mother and child is already a Mother and Child. And that is also because those religious images were conceived and developed in relation to the ordinary, the cotidian, the human. Caravaggio was already there in his conflation of the sexual and the devotional.

After Manuel‘s surprise at not seeing overt religious imagery, I spent last Sunday at the National Gallery buying reference books to share with the dancers. I had to realise that though I wasn’t bringing that imagery directly into the studio I was already carrying it in my own memory bank and that I needed to give the dancers access to the images even if we disperse them and reimagine them. The point for me is that that iconography informs our daily lives. In love, in calamity we recognise ourselves in those attitudes of religious imagery. Every mother and child is already a Mother and Child. And that is also because those religious images were conceived and developed in relation to the ordinary, the cotidian, the human. Caravaggio was already there in his conflation of the sexual and the devotional.

Every day I start rehearsals with the dancers running through my solo from Mo MhórChoir Féin. When Iarla saw that and the subsequent rehearsals, he remarked that it was as it the dancers were taking on something from me but then dispersing it, exploding it. I don’t know if this is obliteration or expansion but either way, it is something to be investigated.

Every day I start rehearsals with the dancers running through my solo from Mo MhórChoir Féin. When Iarla saw that and the subsequent rehearsals, he remarked that it was as it the dancers were taking on something from me but then dispersing it, exploding it. I don’t know if this is obliteration or expansion but either way, it is something to be investigated.

Iarla also remarked that a biographer had written about him being an atheist now but nonetheless being shaped by a religious tradition. He spoke himself about that religious upbringing as a ‘Big Bang’ – a formative, generating event – and that he lives and creates now with the ‘background radiation’ of that formation. The reference to Big Bang makes me think of the balance between obliteration and expansion that he saw in how the dancers were taking on and evolving my material.

Of course the tradition from which he and I come is a rural Gaeltacht one where community is held together by many ties and customs of which religion is an integral but not exclusive element. When I imagine the crash from which Ireland is still trying to fashion a recovery, I am aware that we have a long history of traumatic and devastating events from which we have had to navigate futures. We have already lost worlds, lives and people. And here we are again.

Sarah Browne’s questions about what she saw in rehearsal have prompted me to think more closely about objects with which the dancers and the work might engage. I was already aware that the big empty studios lacked the physical anchors that orient the movement material. I needed to build an architecture and Sarah has started to imagine what that might be.

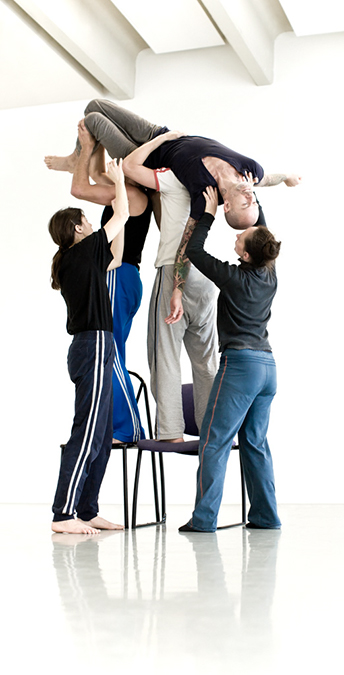

She also prompted an interesting discussion about gender in relation to the dance and to religion. I had been aware the previous week that with Peggy we had an even number of men and women and was sensitive to when the choreography fell into predictable gender patterns. It rarely does but one moment where both Bernadette and Elena were lifted by male partners caught my eye and provoked my discomfort. Of course there are pragmatic physical reasons for why some lifts are best done by the person who is stronger lifting the one who is lighter (not all lifts require strength however and that allows for different possibilities) and in these particular cases the women happened to be lighter. So why was I uncomfortable?

The questions sent me back 20 years to what I was reading at university. I remember in particular Derrida in conversation with Christine Mc Donald in a text called ‘Choreographies‘. Mc Donald starts the interview with a quotation from late 19th century feminist Emma Goldman:

If I can’t dance I don’t want to be part of your revolution

Derrida imagines what the revolution might look like:

As I dream…I would like to believe in the multiplicity of sexually marked voices. I would like to believe in the masses, this interminable number of blended voices, the mobile of non-identified sexual marks whose choreography can carry, divide, multiply the body of each ‘individual’ whether he be classified as a ‘man’ or a ‘woman’

While my work is definitely concerned with cherishing the individual, Tabernacle is beginning to mark a new phase in my understanding of that individuality. What I respond to in Derrida’s vision is the fluidity of that individual experience carried across bodies of many. This is a version of the mass that it not threatening to and consuming of the particular experience. Instead the multiplicity is able to amplify and set in motion that particularity. In practice, it reminds me of Iarla’s observation of the dancers carrying and dispersing the input I’ve given them. I see also their delicious individuality but carried in a choreography that blends that individuality into shifting arrangements and mutual accommodations. It’s not about creating a fixed structure but about making a work that remains open and mobile.

Post a Comment