Hilary Carty, Director of the Clore Leadership Programme asked me if I would share a video of my thoughts on leadership in the current crisis. I wasn’t sure I had anything to offer, and didn’t want to be adding to the digital noise, but I thought I’d share my experience of uncertainty and vulnerability as a truth from which to build.

Yearly Archives: 2020

A video by Clwstwr on the Moving Layers Project

Moving Layers – Week 2

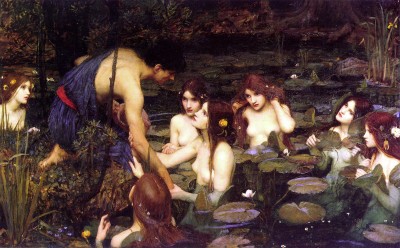

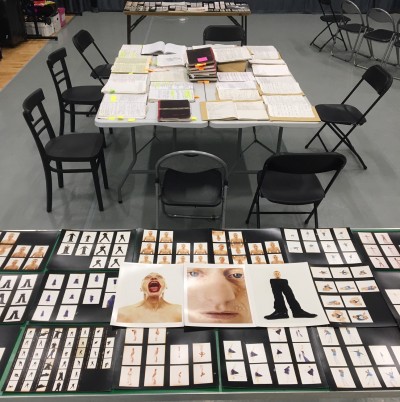

Coming back to our Moving Layers R&D, I felt some pressure to round it up, to turn it into an outcome, despite realising that two weeks of a very new kind of R&D was very preliminary. Often when we do R&D for a performance, the research is towards a relatively defined destination with relatively familiar tools and resources: the trajectory of the research is linear. In this case, however, the research and the consequent learning was multi-dimensional: we aimed towards some kind of scratch performance outcome, but that was to give ourselves forward momentum rather than a destination. We didn’t know what the performance outcome/event/experience would be. Our previous sharing suggested that the value of dancing remained at the heart of the work but what else could it be? We didn’t know what form it might take, nor what its content/subject might be. Through Hylas and the Nymphs we gave ourselves a focus (seduction, immersion, desire, fluidity, transformation) that also reflected on the process we were involved in, allowing us to see ourselves considering the interface between the live and the augmented and to see bodies being transformed by the interaction with the technology.

Alongside that evolution of process and content, we also continued to get to know each other. With a new duo of dancers – Theo Clinkard and Folu Odimayo – there were conversations to repeat and in the process deepen as we introduced the process to new people and opened to their perspectives. We continued to work out the rhythms of a rehearsal process with dancers and, in this week, a composer (Tic Ashfield) and a developer (Roderick (Rob) Morgan) in the room.

While much composition and coding could happen before or elsewhere, I know from working with Tic (and with Alma Kelliher) the benefit of having the composer in the room, soaking up information that might not be articulated otherwise, sharing physical and affective space. I think the same is true of having a developer in the rehearsal room. Even though Rob Morgan was busy with the coding, often focused on the laptop rather than the moving bodies, having him with us, sensing the energy in the room, created human links that fed the work. It’s the preciousness of affective, kinaesthetic, embodied connections that we took care to maintain in our R&D, despite the seductions of the augmenting technology. We wanted to use the technology to help an audience to step from viewing to dancing, to use the distraction of augmentation to give people three-dimensional scripts and visual rhythm to prompt their movement.

We also discovered that for an audience, the technology – in particular the Hololens headset – can stimulate the viewers’ imaginations even if they’re not wearing it. They imagine what the Hololens wearer is seeing, maybe desire to see, and sometimes their imagination is richer than what the technology is capable of delivering – though it’s clear that for other viewers whose first reaction to putting on the headset is ‘Wow!’ that there is pleasure and surprise.

Doing this research from the experience of people who identify as gay – predominantly but not exclusively gay men – was a deliberate choice to propose that generalisable knowledge could be created from minority experience. Despite its apparent openness to transformation, much immersive digital technology is developed from a heteronormative position, with assumptions about who is active, who is watched, who is subject and object. As dancer and dance tech pioneer Ghislaine Boddington commented: “A high proportion of VR content is male heterosexual porn.. […]Content creators need to think in a much more diverse way”. Of course all generalisations are open to challenge and in this instance, it was the female in the room – Tic – who was the most avid gamer. With gay men of different generations (in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s – pre and post-PREP generations,) of different different cultural origins, it wasn’t as if we approached the research from a single perspective. What might seduction mean to those of use more comfortable or at least more familiar with cruising or flirting online rather than in ‘real’ space [and in which particular places rather than abstracted ‘space’ – on a street, in a club, in a studio, in a classroom?]. While the perspectives we brought to bear on the research were neither homogenous nor exclusively ‘gay’, it was important to be in an environment where it was possible to bring our gay experiences into play, with sufficient trust and mutual understanding to be able to delve into the differences between our experiences too.

Doing this research from the experience of people who identify as gay – predominantly but not exclusively gay men – was a deliberate choice to propose that generalisable knowledge could be created from minority experience. Despite its apparent openness to transformation, much immersive digital technology is developed from a heteronormative position, with assumptions about who is active, who is watched, who is subject and object. As dancer and dance tech pioneer Ghislaine Boddington commented: “A high proportion of VR content is male heterosexual porn.. […]Content creators need to think in a much more diverse way”. Of course all generalisations are open to challenge and in this instance, it was the female in the room – Tic – who was the most avid gamer. With gay men of different generations (in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s – pre and post-PREP generations,) of different different cultural origins, it wasn’t as if we approached the research from a single perspective. What might seduction mean to those of use more comfortable or at least more familiar with cruising or flirting online rather than in ‘real’ space [and in which particular places rather than abstracted ‘space’ – on a street, in a club, in a studio, in a classroom?]. While the perspectives we brought to bear on the research were neither homogenous nor exclusively ‘gay’, it was important to be in an environment where it was possible to bring our gay experiences into play, with sufficient trust and mutual understanding to be able to delve into the differences between our experiences too.

Having just seen the film Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire which BFI describes as ‘a countermeasure to centuries of the male gaze in art, reaching out to other female artists and poets in its study of desire and creation’ , it’s clear that these questions of gaze, of seduction, of the brilliance and danger of being ‘on fire’, or ‘immersed’ are not exclusively male nor heterosexual. Working on this research has allowed an engagement with the intimate, the playful, the poetic, as well as the risky, the provocative and the uncertain. As well as continuing to develop our particular experience for audiences and participants, I think there’s scope for us to share this approach to immersive and augmented technologies with other makers, developers and technologists to help to shape a more inclusive, diverse and embodied approach to how these technologies evolve and in evolving, change us.

Having just seen the film Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire which BFI describes as ‘a countermeasure to centuries of the male gaze in art, reaching out to other female artists and poets in its study of desire and creation’ , it’s clear that these questions of gaze, of seduction, of the brilliance and danger of being ‘on fire’, or ‘immersed’ are not exclusively male nor heterosexual. Working on this research has allowed an engagement with the intimate, the playful, the poetic, as well as the risky, the provocative and the uncertain. As well as continuing to develop our particular experience for audiences and participants, I think there’s scope for us to share this approach to immersive and augmented technologies with other makers, developers and technologists to help to shape a more inclusive, diverse and embodied approach to how these technologies evolve and in evolving, change us.

Moving Layers – Clwstwr R&D NDCWales

Moving Layers is an R&D project I’m doing for NDCWales with experience-designer Rob Eagle. It’s a project funded by the Clwstwr programme, a partnership between Cardiff University, University of South Wales and Cardiff Metropolitan University ‘to create new products, services and experiences for screen’. The Cardiff partnership is one of the UK government’s Creative Industries Clusters Programmes,

part of the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund that is being delivered by the Arts and Humanities Research Council on behalf of UK Research and Innovation. This unprecedented research and development programme will keep the UK at the cutting edge globally; creating jobs, developing talent and driving the creation of products and experiences that can be marketed around the world, significantly contributing to UK economic growth, both nationally and regionally. (Clwstwr)

It’s good to note the economic imperative that’s driving this opportunity but at this stage, what Clwstwr has provided us with is a valuable opportunity to do some very initial research on how Augmented Reality and dance might work to produce new kinds of dance experience and new ways of experiencing it. National Dance Company Wales has proposed that we:

will prototype an experience that enables a diversity of people to witness and participate in dance stories that change the audience/performer relationship and that connect people to their own physicality. This project will explore knowledge-exchange between choreographers, academics, mixed reality designers and programmers to build a basic demonstrator that addresses a longer-term ambition to connect to audiences outside the traditional touring model and develop vital new markets for dance. (Clwstwr)

The reference to connecting people to their own physicality was particularly important for me since my experience of Virtual Reality experiences was that they drew people away from their physicality (sometimes, as in the case of pain relief VR experiences, for beneficial reasons). But what we in dance have an expertise in, is in liveness. Even when working with Dearbhla Walsh on dance films, it’s always been a digital mediation that connects people to the visceral sensuality of movement in others and in themselves that’s been a goal. With Augmented Reality, it feels that there is more opportunity to main that connection with the organic while adding the extra possibilities of the virtual.

I came across Rob Eagle’s work through Twitter. I noticed that he was developing AR experiences with a queer edge: his Through the Wardrobe project invites people to inhabit gender fluid and gender non-binary experiences. I was also aware of his documentary work on identity in gay fetish communities and the intersection of the queer and the technology attracted me. For NDCWales, working with Rob could be at once an opportunity to innovate in formats of dance creation and presentation and it could also bring gender diversity and sexuality into greater focus in the Company’s creative work.

Given it was a new relationship, Rob and I spent some time discussing how we would start and what would be a point of common departure for our first week of R&D in the studio. We were interested in a notion of fluidity and liquidity, something that linked the distinctive quality of dance that can keep ideas, experiences and consequently identity in motion, and the potential of an augmented reality to transform experience. In that idea of fluidity, for me was also a sense of the queer as a verb – an action of deviation, of motion – rather than a noun – a label and fixed identity. From the discussion about fluidity and fluids emerged a an acknowledgment that for a gay man of my generation, fluid was something to be protected against. It related to desire and also death. For a younger generation, that might no longer be the case, but we realised that the language of seduction, desire and danger connected our bodies and the technology.

My research in preparation for the first week of studio time with Rob and with dance-artists Meilir Ioan and Rob Bridger, took me from the Taoist understanding of water (the element of winter, of inward reflection, of multiple forms that imbalanced could mean vacillation and indecision), to the Welsh Ceffyl Dwr – the mythological water horse that sometimes draws unsuspecting riders to their doom (something in the solid corporeality and power of a horse also transformed into water still resonates) and a reading of Greek water-related creatures that brought me to the Pre-Raphaelite painting of Hylas and the nymphs.

My research in preparation for the first week of studio time with Rob and with dance-artists Meilir Ioan and Rob Bridger, took me from the Taoist understanding of water (the element of winter, of inward reflection, of multiple forms that imbalanced could mean vacillation and indecision), to the Welsh Ceffyl Dwr – the mythological water horse that sometimes draws unsuspecting riders to their doom (something in the solid corporeality and power of a horse also transformed into water still resonates) and a reading of Greek water-related creatures that brought me to the Pre-Raphaelite painting of Hylas and the nymphs.

The painting, by John William Waterhouse, depicts Hylas, the lover and companion of Hercules, who has gone to fetch water on a stop off during the voyage of the Argonauts. Hylas was so beautiful that the nymphs of the pool wanted him and seduced him into the pool where he was trapped/elevated in immortality. Hercules was distraught when he didn’t return and called for him. He only heard the words Hylas, Hylas, Hylas come back to him.

The story is one of seduction, desire, immersion, danger, loss and suspension (in time). As with most stories of desire it is one of repetition (Hylas, Hylas, Hylas). Hercules loses Hylas but gains him because he has murdered Hylas’ father.

The story is one of seduction, desire, immersion, danger, loss and suspension (in time). As with most stories of desire it is one of repetition (Hylas, Hylas, Hylas). Hercules loses Hylas but gains him because he has murdered Hylas’ father.

The painting suspends the moment of seduction just before the immersion. Apparently, Waterhouse used two models for the seven nymphs so there’s repetition there too. The painting gained notoriety recently when it was taken from permanent display at the Manchester Art Gallery as part of an intervention by Sonia Boyce: ‘The act of taking down this painting was part of a group gallery takeover that took place during the evening of 26 January 2018. People from the gallery team and people associated with the gallery took part. The takeover was filmed and is part of an exhibition by Sonia Boyce, 23 March to 2 September 2018′. The intervention aimed to challenge the ‘Victorian fantasy’ of the female body as either a ‘passive decorative form’ or a ‘femme fatale’. (MAG)

It was reinstated after public outcry at what was regarded as censorship and perhaps a misreading of what could also be regarded as a depiction of active female desire rather than simply the presentation of passive female nudity.

I don’t feel the need to resolve all of these tensions in the painting, in its inspiration, genesis and reception. It’s still a useful focus for teasing out the appeal and dangers of engaging with virtual reality and bodily desire. And as Manchester Art Gallery acknowledged after their experiment: ‘the painting has been a barometer of public taste since it was painted in 1896 and continues to be so.’ (MAG) The notion of the pool as the place of immersion provided us with a spatial reference for the choreography. And if at moments, Rob and Mei and I imagined ourselves seducing the beautiful young man, this queering of the apparently heterosexual image (already queer in fact given Hercules and Hylas’ intimacy) allowed it to be a useful resource. Adrian Rifkin’s response to the Manchester Art Gallery removal acknowledges the latent queerness of the work: ‘ as a young gay man growing up in 50s and 60s Manchester – and queer art historian to-be – Hylas was one of my lifelines to an imaginary world of desire found in images of men.’

Forty years after Laura Mulvey’s critique of the male gaze, which was an attempt to understand pleasure, not to outlaw it, this rather trivial gesture can only be understood as politically shallow. But more than that, as an insult to someone who has lived at a tangent to the heteronormative discourses of which, indeed, it is a fragment. (Rifkin)

Our week involved talking and dancing – and delightfully I got to watch and to dance with Mei and Rob Bridger. From last year’s Laboratori at NDCWales with Éric Minh Cuong Castaing, I learned that we could think about working with digital technologies that allowed us to see their impact, their ethics and their ideologies. Inspired by that approach, I wanted us to invite our audience to be immersed at moments, but also to see immersion, to imagine immersion without augmentation and to experience the physical impacts of immersion in others. These layers of experience, as much as the layers in the experience, seem like valuable ingredients if we are to understand and appreciate the full impact of augmented and immersive realities.

It was clear from the feedback to our sharing that the experience provokes different kinds of desire – a desire to know what the other sees, to be involved, to watch it unfold. These are not new points of view, as lighting designer Caty Olive pointed out, but what the technology does is augment this familiar experience and give us an opportunity to reflect it and reflect on it.

Nigel Charnock’s Lunatic for NDCWales

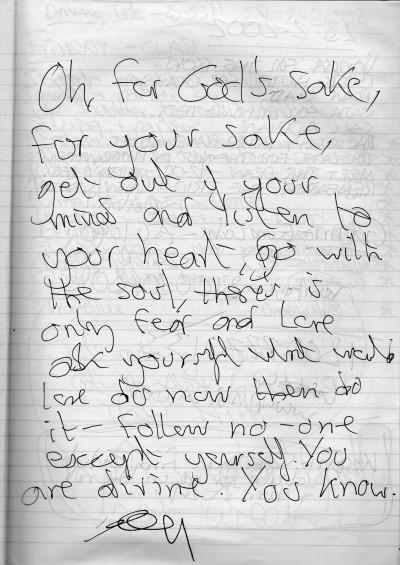

The energy that Nigel Charnock managed to dance, scream, laugh and whack into the world still reverberates despite his too early death 7 years ago. Last week, the dancers of NDCWales, many of whom wouldn’t have been aware of Nigel’s work, received that energy channelled through Jo Fong and through some of Nigel’s archive that was on loan as part of the process of reviving Lunatic, a piece Nigel made for the Company in 2009. Jo was one of the original cast and has, with Graham Clayton Chance and Nick Mercer, who are looking after Nigel’s legacy, and with Gary Clarke who also danced in Nigel’s work, helped plug the NDCWales dancers into the specifics of Lunatic and into the wider source of Nigel’s work. It’s been exciting to see the dancers take the permission and the challenge that Nigel’s work offers to everyone – performers and audiences – to be more, to risk going further and to have fun in the process.

The energy that Nigel Charnock managed to dance, scream, laugh and whack into the world still reverberates despite his too early death 7 years ago. Last week, the dancers of NDCWales, many of whom wouldn’t have been aware of Nigel’s work, received that energy channelled through Jo Fong and through some of Nigel’s archive that was on loan as part of the process of reviving Lunatic, a piece Nigel made for the Company in 2009. Jo was one of the original cast and has, with Graham Clayton Chance and Nick Mercer, who are looking after Nigel’s legacy, and with Gary Clarke who also danced in Nigel’s work, helped plug the NDCWales dancers into the specifics of Lunatic and into the wider source of Nigel’s work. It’s been exciting to see the dancers take the permission and the challenge that Nigel’s work offers to everyone – performers and audiences – to be more, to risk going further and to have fun in the process.

When I started dancing in the nineties, I was aware of Nigel as a fierce performer – fiercely funny, fiercely physical and fiercely moving. I was also aware that he was gay and that his dancing in DV8 gave me a permission to explore a life through my dancing that might not have been possible otherwise. Something in his energy also made it clear that, in the time of Section 28 and the AIDS crisis, that the life I might live had to be fought for with energy and determination. I saw that insistence in his performances. What I didn’t realise at the time is that before helping to found DV8, Nigel had been an equally iconoclastic performer with Ludus, a dance in education collective of the most radical kind. I came to know Nigel’s solo work by the time I was in dance training myself and remember the thrill of being one of the students at The Place chosen to dance in a drama called Citizen Locke (based on the life of the philosopher) for which Nigel choreographed some scenes – thrilled and intimidated, because I felt in Nigel a standard to be achieved. We wore very brown clothes.

Later, when I was beginning to choreograph, I had the opportunity to ask Nigel to be a mentor to me when I did a residency at Firkin Crane, working with Rebecca Walter and Ríonach Ní Néill on a piece called Vespers. I didn’t quite feel adequate to his attention at the time and yet despite my sense of inadequacy, I knew that what he proposed, by being the studio, by asking me difficult questions, by warming up in the morning with such immediate and relentless vigour, would remind me that there was more to for me to give in everything I did.

When I arrived at NDCWales as Artistic Director, I started to think about the choreographers that I thought it would be good for the Company to commission. But I also knew that one of the distinctive qualities of a repertoire company is repertoire – a sense of history that in our contemporary art form isn’t always cherished. But proposing to revive Lunatic, a work Nigel made for NDCWales in 2009 , wasn’t about just about history. Lunatic, like so much of Nigel’s work, explores sexuality, gender and national identity. The energy of that work grew out of the oppressive society and politics of eighties and nineties Britain to which Nigel’s work responded. We might have thought we’d moved beyond that context and therefore the fight that Nigel’s work represented. But in 2019, that context, questions of national, gender and sexual identity, threats to the rights of minorities (and in the case of women, majorities) around the world, make Lunatic as relevant as ever it was. And I love that a queer working-class choreographer who grew up in North Wales, trained in Cardiff and whose ashes are scattered across the Bay from the Dance House can still provide a radical energy to NDCWales work.

When I arrived at NDCWales as Artistic Director, I started to think about the choreographers that I thought it would be good for the Company to commission. But I also knew that one of the distinctive qualities of a repertoire company is repertoire – a sense of history that in our contemporary art form isn’t always cherished. But proposing to revive Lunatic, a work Nigel made for NDCWales in 2009 , wasn’t about just about history. Lunatic, like so much of Nigel’s work, explores sexuality, gender and national identity. The energy of that work grew out of the oppressive society and politics of eighties and nineties Britain to which Nigel’s work responded. We might have thought we’d moved beyond that context and therefore the fight that Nigel’s work represented. But in 2019, that context, questions of national, gender and sexual identity, threats to the rights of minorities (and in the case of women, majorities) around the world, make Lunatic as relevant as ever it was. And I love that a queer working-class choreographer who grew up in North Wales, trained in Cardiff and whose ashes are scattered across the Bay from the Dance House can still provide a radical energy to NDCWales work.