From our experience of doing the final E-motional Mapping in Limassol with a big group of people following us, we knew that such a crowd of specific spectators had a big impact on how we experienced our process and on how we manifested that experience. Having a large gathering of people on the streets has the practical impact of changing the dynamic and energy of the environment. It occasionally obscures the geometry of the quintet and so challenges our ability to compose with the shape of our relationship in the city. Moreover, even though we are clear that this work is not a performance, the crowd of designated spectators which has gathered specifically to follow us (as distinct from the casual spectators who encounter us on the route) creates a frame that we are drawn to fill. And so with the spectators in Limassol we expanded our physicality and accepted being visible in a more performative way.

Aware that more than 40 people had booked to join us for our final walk in Bucharest, we considered carefully how we should organise their experience and ours. The sensitivity in the area about the destruction of Matache meant that it was necessary for the E-motional Bodies and Cities organisers, Cosmin and Stefania, to get a permit for our route. The problem wasn’t so much our exploration of the neighbourhood, which we conducted daily without official sanction, but the large group that followed us that might be construed as a demonstration. We initially asked for permission to follow a route through the Matache market and through some less sensitive local streets. Only the route through the streets away from Matache was permitted.

So that we wouldn’t have a group of 40 following us however and so that the powerful experience of visiting Matache wasn’t completely lost to our process sharing, we decided to split the group in two. One would find us on the sanctioned route, doing what for the purposed of official legibility was called a ‘dance parade’. The other group would be divided into smaller units of 5 (reflecting our geometry) and sent to the market with tasks that would help those participating experience for themselves the process we engage in and also bring back to the bigger group a sense of the market. Given that the ‘dance parade’ would take place in the permitted streets and that others were simply visiting a market, we didn’t anticipate any problems and printed instructions accordingly (thanks to Luke’s combination of artistic and practical design skills).

However on the morning of our presentation, Cosmin and Stefania received a call from the police requiring them to confirm that no one would be visiting the market and rather than put them into any legal jeopardy we had to abandon our plan to send 20 people to the market, knowing that the police’s alertness to our activity would make such a group too visible. We didn’t lose the market completely however but chose a smaller number of people to experience the market individually and therefore less conspicuously (although some who took photos were spotted and warned from doing so again). This solution wasn’t ideal but the whole situation did remind us that our work of placing the body in relation to the city has an unavoidably political dimension. Aptly, the theme for our research in Bucharest was the politics of the body and though we hadn’t chosen to deviate from the process we developed in Dublin and Limassol to specifically address that theme, the process found its way to foreground it nonetheless.

Having a large group follow us changed our walk in Bucharest as it had in Limassol: so did the presence of plain clothes and uniformed police officers who followed us throughout. The plain-clothes officer filmed everyone at the start of the walk probably to have a record of the participants in case of any trouble. The police officers were not unfriendly, although their guns were disconcerting. I had found a small plastic gun (with Made in China stamped on it) earlier in the week and secreted it under a bench in the dog park on our route, along with a broken mirror and a piece of honey-comb. I hadn’t really known why I was keeping the little gun that I would visit on our walks each day. I understood the broken mirror as a simple metaphor for our fractured reflections of the city in our walking practice and the empty honey-comb connected to our group activity and to the many holes that distinguished our route in the city. Having the policemen and their guns finally gave a post-facto purpose to my impulse. Early in the walk, the policemen found me covering Luke with crumbled plaster.

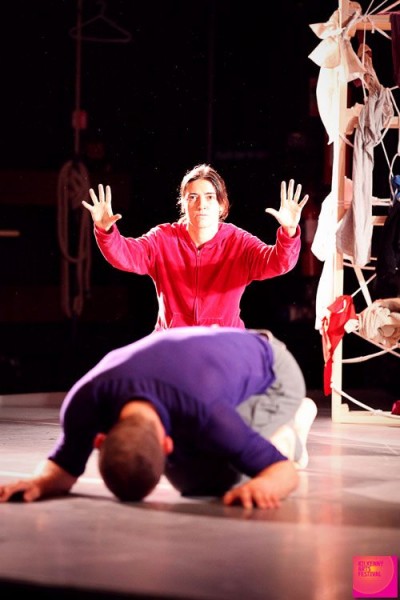

I had found him lying on the side of the street and, reminded of our interaction in the Carob Factory in Limassol where I buried him in carob seeds, I found what I could to ‘bury’ him again. The police asked if everything was ok and if this was part of our dance. I said yes. But Luke’s lying on the ground prompted anger in some local onlookers who berated the police for allowing this to happen. A local elderly lady however came to help Luke to his feet, not distressed, not angry but careful.

The police passed me a little later as I held a position waiting for our quintet to advance. I asked them if everything was ok. The one who spoke English said ‘yes’ but that he didn’t understand what we were doing. I explained that we had been experiencing this route for the past week, its details, atmospheres, architecture, history and that we were communicating what we perceived in our bodies. He said he understood. As we progressed, I felt these policemen become guardians as much as surveillance.

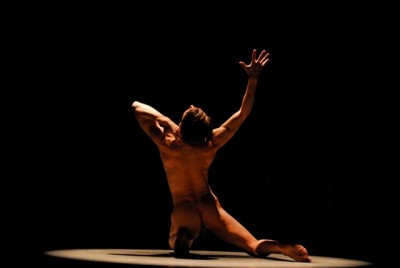

As aspect of my nascent studies in human geography that connects directly and helpfully to my work has been the understanding of space not just as a set of physical parameters but as a nexus of contested histories, and imagined futures experienced through the body as an emotional, psychological and social entity. Our mapping of these particular streets in Bucharest is not scientific. We change the experience of those streets for one another just as much as a crowd of spectators does. We bring our shared history, our memories of other cities as well as our impressions of other parts of Bucharest and ‘find’ those memories again in these particular streets.

As we walked on Saturday I noticed Arianna start to dance to the music that was being played from a car radio on the street. The memory of our group boogey outside the ice-cream shop/café in Limassol where the owner would wait for us to pass so he could turn up the music for us. Without saying it, we all recognised this moment and found our Limassol boogey on the streets of Bucharest.

It pleased me very much that Romanians recognised their city in our group walk, feeling its tensions, textures and possibilities through us. It pleased me that Madalina was proud that we had achieved this manifestation in her city. It pleased me also that others identified the challenge to a capitalist expediency and efficiency that our slow and careful noticing of the environment might represent. Our walk is not a ready commodity. It doesn’t come packaged in a performance-friendly arc of narrative or rhythmical development. It is not homogenous. Olga, Luke, Madalina, Arianna and I engage in the process in our distinct ways and and the group practice is an amalgam of that diversity rather than a uniformity imposed on each individual. A hurling, rugby or soccer team is not made only of backs or forwards.