It’s over a year since Starlight started as a research residency at The Firkin Crane in Cork. I worked with Matthew Morris, intending to make a solo with him. An alignment of stars meant that Peggy Grelat Dupont came too, visiting for a few days in our first chance to work together. We’re building on that research now to make Starlight for the Cork Midsummer Festival in June this year. It’s now two solos and will take advantage of Matthew’s new aerial skills. But while we’re rehearsing in London we’re just concentrating of recovering and refining Matthew’s material while building a new vocabulary for Peggy. I’m still getting to know Peggy, her energy, her approach. I’m learning to understand how best to make use of her physicality and her extensive experience and to communicate to her in a way that makes brings the best out of her. Like Matthew, she has worked with some of the most famous choreographers in the world so the challenge for me is to find something new for them, from them, to surprise themselves and me. You can see a little of how we’re getting on here:

Yearly Archives: 2012

Choreographers and control

On Saturday I saw two very different performances that made me think about choreography and control.

In the afternoon, I spent some time at a piece called Stilled, a durational dance piece from Fevered Sleep.

Inspired by the scientific process of X-ray Crystallography, Fevered Sleep’s most delicate piece for adults weaves together dance, light, music and photography to create a meditative cross-artform event exploring perception, movement and stillness.

Accompanied by a live sound and light score, the piece is performed for both for a human audience and for a bank of silent, all-seeing pinhole cameras. Throughout the performance, images are exposed, developed and displayed, to show glimpses of bodies moving slowly in the light. Each image bears witness to dances that have already been and gone, durations of time captured in a single image.Stilled is a meditation on the nature of perception: of taking time to become visible, taking time to be present, taking time to look, and taking time to see.

There were four sensitive dancers in the work but also the choreographer/director David Harradine who entered the performance structure to arrange pin hole cameras that captured diffuse images of the performance.

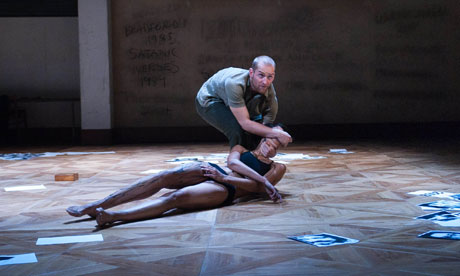

I thought about the choreographer’s role in the work when I watched DV8’s Can we talk about this? at the National that same evening. Can we talk about this? is deliberately challenging. It ‘deals with freedom of speech, censorship and Islam’ building a picture of religiously sanctioned intolerance that liberal western values are too tolerant to challenge. The performers address the audience directly, rarely relating to one another on the stage. There’s a virtuoso quality in their ability to speak complex text while dancing often complex movement patterns. I was moved by sequences such as Joy Constantinides delivery of MP Ann Cryer’s words about honour killings, while Joy balanced a tea cup and saucer as she was manoeuvred through a series of delicate balances by one of the other dancers.

However, there was a tension for me in the work: it seemed to be critical of a religious fascism that controls bodies and minds and yet this superbly executed work relies on a choreographic process that has strictly controlled those dancing bodies on stage. There is no room for surprise in the performance. Everything is thoroughly determined. And in that control I sense the choreographer, Lloyd Newson.

While Harradine exerts control in Stilled, moving the pin hole cameras to determine how the work is viewed, at its heart the work is improvised and even the technology of the pin hole camera is imprecise producing images that are impressionistic, uncertain. Moreover, Harradine allows us to see his intervention. He enters the space and becomes a performer. He makes himself vulnerable to the audience’s interpretative gaze.

Not so Newson whose precise controlling vision is all pervasive in his work. In the programme, Newson talks about how joining a DV8 production being like joining a religion but without God. Maybe there is a god, and it’s the choreographer? Ironically in a work that is critical of dogma, the choreographer’s dogma is what creates such a specific, polished performance. It’s not a work that needs much of me except to receive its message.

With Stilled, however, I felt the invitation to participate, indeed had to suppress the urge to join the dance. It’s a different way to choreograph, a different relationship with the audience, a different set of values. Stilled and Can we talk about this? are both successful accomplished works for me.

But I know which approach communicates the world as I experience it and would like it to be.

Tabernacle: Gabriel Schmitz and Tove Hirth

When we were in residence in Barcelona last November, sculptor Tove Hirth and painter Gabriel Schmitz spent some time in the studio drawing, photographing and absorbing our rehearsals for Tabernacle. Their sensitivity to evocative images of bodies arranged in space meant that they saw so much of the detail of the piece. And their generous seeing was gratifying for me and for the dancers.

Now I am delighted to see some of the results of their seeing emerging in their work.

Gabriel’s latest exhibition at the Galeria Rayuela in Madrid features two paintings that respond to our work: Tabernacle #1 Elena Giannotti and Tabernacle #3 Mikel Aristegui.

They derive from the same image, a moment in the Deposition section, but Gabriel has focused his attention on the arrangement of two bodies in the group of 5 and has separated the two bodies into separate solitary images.

Tove meanwhile has made a series of bronze sculptures that elaborate variations of the single figure in relation to a bench.

To see that Tabernacle survives in and through these works gives me hope that it survives with others too.

Salute to the Merce Cunningham Dance Company

One of the unexpected pleasures of my residency in Chicago before Christmas was a conversation with Bonnie Brooks who was Chair of the Dance Department at Columbia College (and before that President and Executive Director of Dance/USA). She is currently on sabbatical from Columbia and in that time has been traveling with the Legacy Tour of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. She has been asked to document and evaluate the Tour and so has an extraordinarily rich insight into the final year of the company, an insight built upon a long association with MCDC and friendship with Cunningham. I’d intended to talk to her about Tabernacle and my work, but hearing her talk about Cunningham was much more interesting. Besides the more she talked about what mattered in Cunningham’s work, the more I recognised what values I share with it. I write this making no claim to ceaseless innovation of Cunningham’s work but simply a recognition of influence in what might look like very different work.

I was reminded of this reading David Velasco’s review of the final MCDC performances. He describes the necessity for him as a spectator to make choices, to acknowledge his own participation in making the performances. He enters in the work rather than simply observing it.

I have described Tabernacle as another Bodies and Buildings piece since I imagine it as a kind of structure (originally the tent where the Israelites encountered God, or for Catholics the small box that contains the consecrated host). The choreography creates a space but the work depends on people – performers and audiences – to enter in to that space. It offers a possibility but I understand that for some that possibility feels like a challenge.

Velasco writes in his review:

It was impossible to take in. I’m not the first to note the challenge of trying to see Cunningham choreography. The dances themselves are built to kill lazy looking: You have to make decisions. The Events, particularly those with multiple stages (an invention of the past decade), amplify this effect. This wasn’t theater-in-the-round; it was theater-in-the-surround.

Seeing and moving were simultaneous. (Even when you were standing still you were deciding to stand still; you might as well have been moving.) This made you, to some small extent, like the dancers, but also made you all the more alert to the scission between dancer and audience. To different kinds of seeing and moving. To different relationships between seeing and apprehending. Theirs and yours. Yours and everyone else’s.

Over and over again there was the question: How should you see? Should you turn on your eidetic memory, so as to “return” to it later, or turn off your camera-eye and lose yourself in the mix? Should you stand in one place and let it unfold in a single grand, cinematic sweep? Do you sweep the floors hunting for the “best” bits? What are the “best” bits? What do we do with this seeing? “That is the crucial transition, from seeing to entering,” Jill Johnston wrote in a review of the debut of Cunningham’s Aeon fifty years ago—which at least had a nice ring to it, a useful koan. The urgency of these questions about experience became a frame for the experience; that movement of “entering” was also an exiting. Every looking-decision was a goodbye to other possibilities, a million minigoodbyes to set you up for the big one.

After fifty minutes, the fourteen dancers, all dancing across the platforms, simply walked off those black Marley stages with the same quiet authority with which they’d mounted them. The lights and music quit, and that was it.

“Well, so what do you do after you’ve witnessed the end of modern dance?” a friend asked, without a trace of irony. Someone raised a glass. And suddenly it was a new year.

Only you: Teatr magazine

After my residency in Poznan last year, I was invited to write an article for the Polish journal Teatr. I’ve just received a copy:

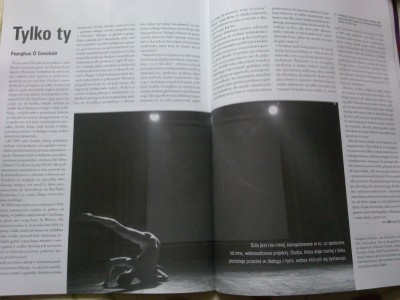

Only you

Fearghus Ó Conchúir

Last January, as part of a research opportunity at The Arts Foundation in Poznan, I found myself alone in the studio and realised that creative solitude was familiar to me. The sense of being on my own in a space was reinforced by the fact that I could hear upstairs the thirty dancers who were participating in a workshop by David Zambrano. His dance work starts in the middle of people, a large fiesta of wheeling energy and activity; mine starts with an individual in a space. However, I’d suggest that the solo is no less an engagement with the social than is more populated work. That individual who sets him or herself a little apart remains in dialogue with those from whom s/he is at a distance.

Since 2005, I’ve been researching work about the relationship between bodies and buildings, particularly in the context of rapid urban change. This research has resulted in a number of group performances, some for film (Three+1) and some for the stage (Niche), but the primary tool in that process has been my own solo experiences of site specific dance that I’ve created for online distribution on Youtube, facebook and my blog.

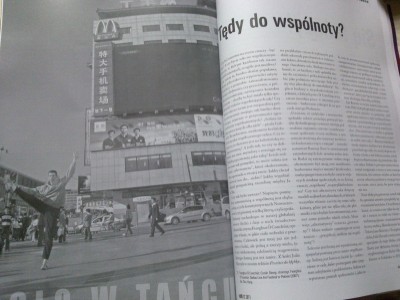

In 2009, I did a residency in Feijiacun, an artists’ village north of Beijing (not far from Caochangdi, the village where Ai WeiWei has his base). The area had been given to agriculture and small villages but the boom in the Chinese art market created an expansion of Beijing’s gallery scene, pushing artists and newer galleries from the increasingly expensive downtown property to this less central territory.

By 2009, however that boom had stalled, partly because the international market was already saturated by Chinese visual art of variable quality, partly because the global economy was in trouble despite China’s ongoing development. The impact of this art market crash was that a number of big building projects near Feijiacun had stalled. Huge buildings that had been destined to become art galleries remained unfinished. And because China has so much land it is careless about this unused space and allows it to be empty and fallow. So, building on a strategy I had already employed on building sites in Dublin’s Docklands, on Martello Towers in Fingal and in former fascist holiday camps in Northern Italy, I would sneak in to these buildings and record short solo dances there. The dances were always fired by a delight at being able to appropriate that kind of magnificent space for my work but also fuelled by an adrenaline born of the knowledge that I had no official permission to be there. The resulting rough video material, shows a solo dancer in a gloriously large borrowed environment that tempts one to focus on solitude. But for me the importance of this solo intervention is the relationship between the dancer and the space and by implication the relationship between the dancer/citizen and the larger economic and social structure that the building makes concrete. When I danced in these unfinished buildings in Beijing, I felt like I could insert myself in the narrative structure of the global financial crisis, as it was manifest there. In doing so, I asserted that I’d survived so far: “Look I can move, I’m still here”. More than that, I demonstrated that creativity could continue, indeed build on the leftovers of that economic crash.

When I started this strategy of solo dances conceived in relation to architectural structures and to the financial, social and political conditions upon which those buildings are constructed, it was in a confident Ireland that believed its myth of economic invincibility. In 2007, as Artist in Residence for Dublin City Council, I spent a lot of time dancing on the street corners, building sites and waste ground of the city’s Docklands that was then undergoing massive redevelopment from old working class inner-city dereliction to aspirational aluminium and glass apartment blocks and office spaces for the much international financial service industry. When I would dance then, I felt that I wanted my body to gather and express the life and experience that this new development was obliterating.

I also wanted to stake a claim in this new version city living for individual, idiosyncratic self-expression. This seemed particularly necessary as parts of the Docklands that had once been public space were now becoming the property of developers whose security cameras and guards defined acceptable behaviour not only in their buildings but in the ‘open’ spaces around them.

When I made the videos in 2007, there was a sadness of something lost in the solo dancer’s confrontation with the architecture that grows around him. But when I look at them now, that context is changed radically: after the economic crisis in Ireland the redevelopment of the Docklands has come to an uncomfortable halt as reckless lending by the banks, reckless speculation by property developers and poor planning supervision by national and local politicians has been exposed. The videos may capture a moment at the end of the Celtic tiger boom but they also anticipate its demise. The apparently solo dance is clearly a much more complex dialogue between dancing body and shifting socio-political and economic context. When the latter changes, the dance does too, even though the body’s choreography, fixed by the recording on my mobile phone, remains unaltered.

Solos cannot be a retreat from engagement. Even the gesture of flight to the margin has no meaning except in relation to a central place to which the margin is irrevocably related, helping to define that central space even if it moves away from it.

‘Il n’ya pas de hors texte’, Derrida reminds us and in doing so makes a space for that single dancing human to address his work to the socio-political and economic forces in which his movement is implicated but whose articulation might just be challenged by a new choreography emerging through this solo body.

Note: The videos referred can be viewed in the archives of www.fearghus.net/blog from May 2007 onwards. A exhibition of Fearghus’ video work, Bodies and Buildings, will be exhibited in Rua Red Gallery,Dublin from September 2011.